Multi-Modal Navigation Tools

Improving User Information For Walking, Cycling and Public Transit

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Updated 23 March 2016

This chapter describes wayfinding improvements and other multi-modal navigation tools that provide guidance for walking, cycling, driving and public transit use.

Description

Multi-modal Navigation Tools can include signs, maps, guidebooks, smartphone applications, websites and electronic devices that provide information on journey planning, wayfinding and travel options to a particular destination, including pedestrian access, routes, schedules, fares, connections, services, real time arrival information, and key contact information. They can include Travel-time Maps that indicate the time needed to travel to a particular destination by different modes (Lightfoot and Steinberg 2006). Navigation Tools can be tailored for specific types of users or trips, such as commuters, tourists and other visitors, and people with disabilities. To be effective, these tools should anticipate travelers needs, providing desired information when users need it in formats that are easy to access and understand (Levinger and McGehee 2008).

For example, travelers should be easily able to:

· Find transportation service providers’ customer service website and telephone numbers.

· Plan a route from a particular origin to a destination.

· Read route maps, schedules, fares and contact information in digital and printed materials.

· Find guidance for walking to and from bus stops, train stations, bikeshare docks and carshare locations.

· Determine when the next bus or train will arrive.

· Navigate within a bus or train station, including finding the correct platform and services such as washrooms, refreshments and telephones.

· Identify which mode or combination of modes will work best for an individual’s travel needs.

Intelligent Transportation Systems can provide navigation information through mobile telephones and other handheld devices that can access the Internet, determine their own location using GPS capabilities, and provide services such as automatic electronic payment of Transit and Taxi fares, Public Bike rentals, and Parking. These can access websites that provide maps and transit service information, including routes, schedules, fares and real-time bus or train arrival information (www.nextbus.com). Many newer mobile telephones can determine their own location, and so can guide users who would otherwise be lost.

Wayfinding refers to people’s (particularly pedestrian’s) ability to navigate through an area, and to signs, maps, electronic devices, and other information resources that help orient visitors. Wayfinding is particularly important when people walk or cycle through an unfamiliar area, and for traveling through transportation terminals such as bus and train stations, and airports (AIGA 2005; Muhlhausen 2005).

A Multi-Modal Access Guide (also called a Transportation Access Guide) is a document that provides concise, customized information on how to access a particular destination by various travel modes, with special consideration of efficient modes such as walking, cycling and public transport. Such a guide typically includes:

· A map of the area, showing the destination, major roads, nearby landmarks, the closest rail station or bus stops, and recommended cycling and walking routes.

· Information about transit service frequency, fares, first and last runs, and public transportation schedules if possible; plus phone numbers and web addresses for transit service providers and taxi companies. Special transit schedule information can be provided for Events that start and end at specified times.

· Information on how long it takes to walk from transit stations, downtown area and other reference locations to your site. (e.g., “We are twenty minutes by bus from the airport, and five minutes by bike from downtown”).

· Information on how to reach the destination from major transportation terminals (bus and train stations, airports, ferry terminals, etc.). For example, a Guide might include information on airport shuttle services and transit access.

· Access arrangements for people with disabilities on public transport routes and at train stations (Universal Access).

· Availability of Bicycle Facilities, including secure bike parking, showers and change facilities.

· Automobile Parking availability and price.

Navigation Tools can range from a simple map printed on the back of business cards or event invitations, to a special brochure, map, Internet page, smartphone application or comprehensive information packet. This information can also be incorporated into other printed documents, including business cards, invitations, letterhead, brochures and catalogues. They can be included in welcome kits provided to new employees, with information on telework and flextime policies as well as travel options. Navigation Tools may include bicycle and transit maps, or information on how to obtain such maps. Some Guides intentionally exclude information on automobile access and vehicle parking options to discourage driving.

Navigation Tools should be designed for various types of users, which may include staff, customers and clients, tourists and other visitors, conference attendees, delivery services, and people with disabilities. Different information resources may be needed to accommodate different types of users, including special versions for people with disabilities, who speak a different language, who travel by a particular mode, or who travel from a particular area.

Developing Multi-Modal Navigation Tools can be an opportunity to identify ways to improve mobility options to your destination. For example, while gathering information for a Guide you might find that it is currently difficult to walk from a nearby transit station to your site because sidewalks are in disrepair, that a shelter is needed at the closest bus stop, or that there is no secure place for visitors to store a bicycle. Guides should be revised as access options change (hopefully for the better).

There is a growing movement to digitally map and record street infrastructure, in order to provide better wayfinding and navigating information. Open Street Map is one such platform that is documenting this critical information. There is enormous potential for this data to change the way users travel as they can make more informed choices when journey planning. For example, Open Street Map notes sidewalk size, thus allowing pedestrians to gauge the walking environment of a neighborhood.

How It Is Implemented

Navigation Tools can be developed by transport planning agencies, transit agencies facility managers, private companies or a Transportation Management Association. This information can be incorporated into existing documents, such as brochures and invitations. All staff who work with clients and visitors should be familiar with multi-modal access options so they can advise callers on how to arrive by various modes.

Travel Impacts

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools can increase use of alternative modes and reduce automobile travel. Providing better information and more accessible, convenient ways to plan journeys changes the psychology of ‘waiting for the bus or train’. Users feel more secure knowing when their train or is guaranteed to arrive and feel more comfortable navigating a transit system as a result. Ultimately, travel impacts vary, depending on conditions, including the quality of alternative modes and the degree to which inadequate information and encouragement limits their use. One case study found that providing high quality Navigation Tools resulted in a 17% shift from automobile to walking, cycling or transit as employees’ primary commute mode (RTA, 2003). This probably represents the higher end of travel impacts, since it applied when a worksite location was moving. Relatively large impacts may be achieved if Navigation Tools are implemented as part of comprehensive TDM programs that include a variety of improved travel services, incentives and marketing activities. For more information on the travel impacts of improved user information see TDM Marketing.

Table 1 Travel Impact Summary

|

Objective |

Rating |

Comments |

|

Reduces total traffic. |

2 |

Supports use of alternative modes. |

|

Reduces peak period traffic. |

2 |

" |

|

Shifts peak to off-peak periods. |

1 |

May include information on flextime. |

|

Shifts automobile travel to alternative modes. |

2 |

Supports use of alternative modes. |

|

Improves access, reduces the need for travel. |

3 |

" |

|

Increased ridesharing. |

2 |

" |

|

Increased public transit. |

2 |

" |

|

Increased cycling. |

2 |

" |

|

Increased walking. |

2 |

" |

|

Increased Telework. |

1 |

May include information on telework options. |

|

Reduced freight traffic. |

1 |

May include information on delivery options. |

Rating from 3 (very beneficial) to –3 (very harmful). A 0 indicates no impact or mixed impacts.

Benefits and Costs

By improving travel options and supporting

use of more efficient travel modes, Multi-Modal Navigation Tools tend to

support virtually all TDM objectives. Their cost is usually limited to the

financial cost of producing this materials, and some of these costs can often

be incorporated into existing document and website production budgets. Navigation

Tool production costs are often repaid many times over for a particular

organization (e.g., business or campus) if they result in even a small

reduction in automobile trips and parking demand.

Table 2 Benefit Summary

|

Objective |

Rating |

Comments |

|

Congestion Reduction |

2 |

Supports use of alternative modes. |

|

Road & Parking Savings |

2 |

" |

|

Consumer Savings |

2 |

" |

|

Transport Choice |

3 |

" |

|

Road Safety |

2 |

" |

|

Environmental Protection |

2 |

" |

|

Efficient Land Use |

2 |

" |

|

Community Livability |

2 |

" |

Rating from 3 (very beneficial) to –3 (very harmful). A 0 indicates no impact or mixed impacts.

Equity Impacts

By improving travel options, Multi-Modal Navigation Tools tend to help achieve equity objectives. They can be particularly beneficial to people with disabilities and other non-drivers. By providing better information, multi-modal navigation tools can make journey planning and travel more safe, convenient and accessible.

Table 3 Equity Summary

|

Criteria |

Rating |

Comments |

|

Treats everybody equally. |

2 |

Supports use of alternative modes. |

|

Individuals bear the costs they impose. |

2 |

" |

|

Progressive with respect to income. |

3 |

" |

|

Benefits transportation disadvantaged. |

3 |

" |

|

Improves basic mobility. |

3 |

" |

Rating from 3 (very beneficial) to –3 (very harmful). A 0 indicates no impact or mixed impacts.

Applications

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools can be implemented by virtually any type of organization, but are particularly appropriate for TMAs, businesses and Campuses which attract large numbers of visitors, and are located in areas with diverse travel options. A growing number of private companies and start up enterprises are creating multi-modal trip planners (see References and Resources for specific examples).

Table 4 Application Summary

|

Geographic |

Rating |

Organization |

Rating |

|

Large urban region. |

3 |

Federal government. |

1 |

|

High-density, urban. |

3 |

State/provincial government. |

2 |

|

Medium-density, urban/suburban. |

3 |

Regional government. |

2 |

|

Town. |

2 |

Municipal/local government. |

2 |

|

Low-density, rural. |

2 |

Business Associations/TMA. |

3 |

|

Commercial center. |

3 |

Individual business. |

3 |

|

Residential neighborhood. |

3 |

Developer. |

3 |

|

Resort/recreation area. |

3 |

Neighborhood association. |

2 |

|

College/university communities. |

3 |

Campus. |

3 |

Ratings range from 0 (not appropriate) to 3 (very appropriate).

Category

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools Increase Travel Options

Relationships With Other TDM Strategies

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools support and are supported by a wide range of TDM strategies, including Transit Encouragement Programs, Walking and Cycling Encouragement, Nonmotorized Transportation Planning, TDM Marketing, Commute Trip Reduction programs, Special Event Transport Management, Tourist Transport Management, Parking Management, Campus Transport Management, Transit Oriented Development, Location Efficient Development and New Urbanism.

Stakeholders

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools development usually involves local planners, facility managers, transit agencies, private agencies (e.g., software developers) and user groups (e.g., a local cycling organization).

Barriers To Implementation

Common barriers include a lack of leadership and funding, and ignorance by top decision-makers about alternative modes.

Best Practices

Multi-Modal Navigation Tools should be concise and easy to use. Consider the needs and abilities of different types of visitors. Survey visitors to determine how they currently travel, what they know about their transport options to your site, and any transportation barriers they face.

Stakeholders should be involved in developing Multi-modal Navigation Tools. Produce draft materials. Ask stakeholders to review them and suggest improvements. These stakeholders may include:

· Staff who will use and distribute travel information, such as receptionists, personnel managers, sales staff, event organisers.

· Users, such as employees, clients, customers, delivery vehicle drivers, event participants, and others.

· Staff and visitors with disabilities.

· Public transport operators and the local planning officials.

Use graphic images as much as possible, including maps and symbols with bright colors. Coordinate Navigation Tools, for example, by using the same symbol on maps and directional signs. Provide phone numbers or web addresses for public transit and local taxi companies. A variety of information resources may be needed to accommodate different groups. Be sure to update these resources as needed.

Be as specific as possible. Provide information on which train or bus to take, where to get off, and which street to walk on, and where to turn. For example write, “Take the Yellow line to Victoria Station (call 567-8910 for schedule and fare information). Trains run every 5 minutes on weekdays, and every 15 minutes weekends and evenings. We are a 5-minutes walk from Victoria Station. Use the First Avenue Exit. Walk six block west. Turn right on Smith Street (at the fire station), walk two blocks and turn left onto Royal Avenue where the road forks (in front of Oak Elementary School). We are located three blocks west, on the right-hand side of the street.”

Provide encouragement. Incorporate information about using alternative modes such as walking, cycling and transit, and the benefits that result, including financial savings, reduced stress and increased physical exercise (TDM Marketing). Highlight appropriate fare discounts. For example, a Multi-modal Access Guide to a medical center might remind visitors of discounts available to seniors, while a Guide to a recreation center might remind visitors of discounts available to students.

Staff who produce information materials,

such as invitations and catalogues, can have standard multi-modal guidance

information ready to incorporate into documents as needed.

Transportation agencies and authorities should make their route and schedule data

public, so that private companies can make use of their data to create

innovative trip planning tools. Mobile applications like Ridescout, the Transit App and Next Bus

have taken advantage of transportation data to improve how travelers access and

consider their transportation options.

|

Wayfinding Is Not Signage: Signage Plays An Important Part Of Wayfinding – But There's More By John Muhlhausen, Signs of the Times magazine

Even though signage plays an important role in wayfinding, the process doesn't rely exclusively on signs.

The term "wayfinding" was first used in 1960 by architect Kevin Lynch in The Image of the City, where he referred to maps, street numbers, directional signs and other elements as "way-finding" devices. This narrow description may explain the current misunderstanding that wayfinding is essentially the same as "signage."

The two terms are not synonymous. Signmakers deal with designing, fabricating and installing signs. However, wayfinding used to navigate unfamiliar environments, doesn't rely exclusively on signs.

This distinction gained acceptance in the early '70s when researchers discovered that, to understand how people find their way, they first need to understand the underlying process. Architect and environmental psychologist Romedi Passini articulated spatial problem-solving in his books, Wayfinding in Architecture and Wayfinding, People, Signs and Architecture, which he co-authored with wayfinding planner Paul Arthur. Passini and Arthur described wayfinding as a two-stage process during which people must solve a wide variety of problems in architectural and urban spaces that involve both "decision making" (formulating an action plan) and "decision executing" (implementing the plan).

People who find themselves in unfamiliar environments need to know where they actually are in the complex, the layout of the complex, and the location of their destination in order to formulate their action plans. En route to their chosen destinations, people are helped or hindered prior to their visit, the building's architecture and signage. The physical environment, including positive effect in how users perceive the wayfinding system--if it seems easy to use or not.

Faulty sign design can cause navigation problems in unfamiliar environments. Some signs lack "conspicuity," or visibility, because lettering lacks legibility when viewed from a distance. Others contain inaccurate, ambiguous or unfamiliar messages; many are obscured by obstructions or contain reflective surfaces, which hinder comprehension. Consequently, many people don't read signs--often it's easier to ask for directions.

Because wayfinding problems aren't confined to signs alone, they typically can't be solved by adding more signs. Instead, such problems can be unraveled by designing an environment that identifies logical traffic patterns that enable people to move easily from one spot to another without confusion. Signs cannot be a panacea for poor architecture and illogical space planning.

Four Elements Wayfinding needs are best resolved during initial planning stages through a collaborative effort by all design professionals--architects, designers and signmakers--to address a project's total environmental communication. The primary generator of environmental communication, architecture delineates spatial organization, destination zones and information sequencing--factors that spell wayfinding's success or failure. Effective architectural wayfinding clues, provided by roads, building layouts, corridors and lighting, furnish cognitive maps that allow people to quickly grasp the environment. To furnish architectural clues: · Clearly identify arrival points. · Provide convenient parking and accessible walkways located adjacent to each public entry. · Locate information desks within each public entry visible from the front door. · Place elevator lobbies so they can be seen upon entering the building. · Use consistent lighting, floor coverings and architectural finishes in primary public corridor systems. · Situate memorable landmarks along corridors and at key decision points. · Design public waiting areas that are visually open to corridors. · Distinguish public from non-public corridors by using varied finishes, colors and lighting · Harmonize floor numbers between connecting buildings.

Graphic Communication Graphics, such as signs, color coding, maps, banners, brochures and Websites, provide orientation, direction, identification and regulatory information. To achieve effective graphic communication: · Standardize names for all buildings, services and destinations, and display them consistently on all graphics applications. · Use easily understood "plain" language. · Size messages and signs appropriately for viewing distances. · Select letterforms and color combinations that comply with Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Accessibility Guidelines (see New Face to ADA). · Furnish generous spacing between letters, words and message lines. · Provide standardized "you are here" maps of the project that include an overall map of the complex and more detailed maps of specific areas. · Train attendants to mark individualized paths on hand-held maps for lost or disoriented visitors. · Place maps at all parking exits, building entrances and major interior decision points. · Orient maps with building layouts, such as denoting on maps that "up is ahead." · Establish consistency in sign placements and graphics layouts. · Code areas by using color and memorable graphics. · Use established pictographs with words to facilitate comprehension of written messages. · Establish a floor numbering system that relates to a building's main entry and indicate on directories which floors are above and below grade.

Audible Communication Audible communication, as interpreted through verbal instructions, PA systems, elevator chimes and water fountains, plays an important role in wayfinding. Recognizing that 50% of the American population is functionally illiterate (according to a recent study published by the U.S. Department of Education) and that another 15% possess other perceptual or cognitive impairments, audible communication fills an important role in any wayfinding solution. To establish effective audible communication: · Install audible sounds at signaled intersections to indicate safe times to cross the street. · At all public entries and information desks, provide attendants trained as professional greeters who are thoroughly familiar with the facility. · Furnish self-help telephones at all information desks. · Provide patient-transport personnel whose purpose is to guide visitors to their destinations. · Standardize names for all buildings, services and destinations, and use them consistently in verbal communication. · Equip elevators with audible chimes. · Position audible landmarks, such as water fountains, at waiting areas. · Employ audible signs to help locate information desks, elevators, rest rooms and other key destinations.

Tactile Communication Tactile communication, achieved by raised letters, Braille, knurled door knobs and textured floor coverings assists all visitors, not only the disabled. To incorporate tactual devices into a wayfinding system: · Establish "shorelines" and "trails" between major destinations and information areas using materials having differing resiliency's, such as concrete and carpet. · Install "rumble strips" at the landings of stairs and escalators. · Furnish knurled door knobs at all non-public doors. · Provide a raised star symbol on elevator control panels to indicated the ground floor. · Supply raised letters and Grade 2 Braille at elevators and on signs identifying permanent destinations. · Install interactive audio-tactile maps at public entrance lobbies.

Consistent Clues Architects, designers and signmakers must work together from the beginning of a project to create a total environmental statement that provides consistent clues. So, the next time a client asks for wayfinding signage. tell them that wayfinding is not signage – it's more. |

|

Helsinki's

ambitious plan to make car ownership pointless in 10 years Helsinki

aims to transcend conventional public transport by allowing people to

purchase mobility in real time, straight from their smartphones. The hope is

to furnish riders with an array of options so cheap, flexible and

well-coordinated that it becomes competitive with private car ownership not

merely on cost, but on convenience and ease of use. Subscribers would specify an origin and a

destination, and perhaps a few preferences. The app would then function as

both journey planner and universal payment platform, knitting everything from

driverless cars and nimble little buses to shared bikes and ferries into a

single, supple mesh of mobility. Imagine the popular transit planner Citymapper

fused to a cycle

hire service and a taxi app such as Hailo

or Uber, with only one payment required,

and the whole thing run as a public utility, and you begin to understand the

scale of ambition here. That the city is serious about making good on these intentions is bolstered by the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority's rollout last year of a strikingly innovative minibus service called Kutsuplus. Kutsuplus lets riders specify their own desired pick-up points and destinations via smartphone; these requests are aggregated, and the app calculates an optimal route that most closely satisfies all of them. All of this seems cannily calculated to serve

the mobility needs of a generation that is comprehensively networked, acutely

aware of motoring's ecological footprint, and – if opinion surveys are to be

trusted – not particularly interested in the joys of private car ownership to

begin with. Kutsuplus comes very close to delivering the best of both worlds:

the convenient point-to-point freedom that a car affords, yet without the

onerous environmental and financial costs of ownership (or even a Zipcar

membership). But the fine details of service design for such schemes as Helsinki is proposing matter disproportionately, particularly regarding price. As things stand, Kutsuplus costs more than a conventional journey by bus, but less than a taxi fare over the same distance – and Goldilocks-style, that feels just about right. Providers of public transit, though, have an inherent obligation to serve the entire citizenry, not merely the segment who can afford a smartphone and are comfortable with its use. (In fairness, in Finland this really does mean just about everyone, but the point stands.) It matters, then, whether Helsinki – and the graduate engineering student the municipality has apparently commissioned to help it design its platform – is proposing a truly collective next-generation transit system for the entire public, or just a high-spec service for the highest-margin customers. It remains to be seen, too, whether the scheme

can work effectively not merely for relatively compact central Helsinki, but

in the lower-density municipalities of Espoo and Vantaa as well.

Nevertheless, with the capital region's arterials and ring roads as choked as

they are, it feels imperative to explore anything that has a realistic

prospect of reducing the number of cars, while providing something like the

same level of service. To be sure, Helsinki is not proposing to go entirely car-free. (Many people in Finland have a summer cottage in the countryside, and rely on a car to get to it.) But it's clear that urban mobility badly needs to be rethought for an age of commuters every bit as networked as the vehicles and infrastructures on which they rely, but who retain expectations of personal mobility entrained by a century of private car ownership. Helsinki's initiative suggests that at least one city understands how it might do so. |

Examples and Case Studies

To find examples of Multi-Modal Navigation Tools, simply perform an Internet search on “directions, map, bus”.

Business Card Information

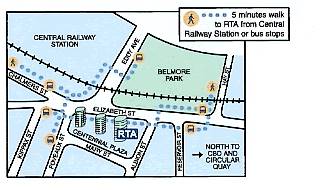

Figure 1 illustrates a simple transit access direction map printed on the back of business cards used by RTA employees.

Figure 1 Business Card Map

This illustrates transit travel directions printed on the back of business cards.

Chicago Bike Guide (www.chicagobikeguide.com)

A mobile phone application that helps cyclists navigate around the city of Chicago using a mobile phone. Users only pay for the data transfer. The system provides:

- Cycle route shown on a map

- Description of the route

- The destination on a map

- Bike safe routes

- Divvy Bikeshare docks and stations

- Chicago Transity Authority and Metra stations

- Points of interest

- Geotagging capabilities

- Utilizes phone user’s current location data

Users indicate their origin and destination by keying in an address or a location search. The system indicates the most direct and safest route option with maps on the telephone screen. It is easy to move the map view and zoom in and out as needed. The system indicates the distance and expected travel time. The route planner can be downloaded at http://www.chicagobikeguide.com

Parent Resource Center Map, Bus & Driving Directions (www.parentresource.on.ca/map.html)

The Parent Resource Centre is located on the first floor of the apartment building (300 Goulburn Private) at the south-west corner of Goulburn Private and Mann Avenue in Sandy Hill. The Centre’s own entrance faces Goulburn Private and is close to Mann Avenue.

By bus: Take bus route #16 to Chapel and Mann.

Walk east on Mann one block to Goulburn Private. If you are using the

Transitway, the Parent Resource Centre is about a ten minute walk from Lees

Station

By car: If coming from the east and heading west on the Queensway, use

the Nicholas-Mann exit and take the right lane (Mann) exit. At the second set

of traffic lights, turn right at Mann Avenue, drive up the hill to stop sign at

Chapel and Mann. Proceed one more block along Mann to Goulburn Private.

If you are coming from the west end of Ottawa and heading east on the

Queensway, use the Nicholas-Lees Avenue off-ramp and keep to the right (Lees Ave.

exit). At the stop sign, turn left onto Lees Avenue and proceed over the

Queensway to intersect with Mann Avenue at the second set of traffic lights.

Turn right at Mann Avenue, drive up the hill to stop sign at Chapel and Mann.

Proceed one more block along Mann to Goulburn Private.

If you are not using the Queensway, Mann Avenue can be reached several ways,

including from Main Street via Greenfield, from King Edward Avenue and from

Range Road.

Parking: There is three-hour street parking on Mann Avenue or other

streets in the neighbourhood. Parking is longer on Goulburn Private and Wiggins

Private (look for posted restrictions).

If you need help with directions, call (613) 565-2467.

Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory (www.lbl.gov/Workplace/Transportation.html)

The Laboratory is in Berkeley on the hillside directly above the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. Our address is 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley CA 94720. To make the Lab easily accessible, the Lab has its own shuttle service that takes people around the site and to downtown Berkeley and the BART station there. Parking spaces are difficult to find here and you will need to prearrange for a parking permit from the person you are visiting.

San Francisco Airport to the Lab by Commercial Shuttle Bus

A number of shuttle van companies provide service from the San Francisco airport. Some travel directly to your particular point of destination. Others drop off their passengers at central points in the East Bay. The airport website has more specific information on “ground transport.”

San Francisco to the Lab by BART

Much easier than traveling by car. Allow yourself 50 minutes for the entire trip from downtown San Francisco. Go to any of the BART stations. Purchase a ticket for $5.30 (the cost of a round-trip between downtown SF and Berkeley as of October 2000). Get on the Richmond line. Take the Richmond line to the downtown Berkeley exit -- not the North Berkeley exit, and not the Ashby exit, just the Berkeley exit. Get off at the Berkeley exit, go up to the street level, and find our shuttle bus stop. It is on the north side of Center Street at its intersection with Shattuck Avenue next to the bank automatic teller machine. You can then take the shuttle bus to the Lab; see the directions for using our shuttle.

More information about BART, including an interactive map of the system and its schedules, is available on the Web (www.bart.gov).

NextBus (www.nextbus.com)

NextBus combines Global Positioning System (GPS) data with predictive software to give public transit passengers accurate arrival time predictions for the next few vehicles, accessible through the Internet (including mobile telephone screens) and bus stop signs.

This helps overcome

a major barrier to public transit use, unnecessary waiting. NextBus allows

users to decide whether to rush to a bus stop, wait, or choose another route or

mode.

RideScout (www.ridescoutapp.com)

Ridescout is a smartphone application that aggregates travel options like

bikeshare, carshare, transit, taxi, driving, cycling and walking into a single

interface. By collecting all services into a single interface, users can

identify which mode is best suited for their given circumstance. The app also

features real-time information, journey planning tools and a notification

service that sends users a ping when it’s time to leave for to catch the bus or

train. Ridescout is the ‘one-stop shop’ of trip-planning apps. Creator and

Founder, Joseph Kopser remarked in The

Atlantic Cities, "Our vision statement is seamless door-to-door

transportation," […] "What I mean by that is every safe, legal, and

reliable way that's out there, we want to bring to you in the palm of your hand

or onto your desktop so you can have all your options."

Trimet Trip Planner (www.trimet.org/ride/planner_form.html)

Portland’s Trimet Trip Planner has always been at the forefront of digital trip planning in America. In 2011, it was the first US transit agency to produce a trip planner that combined walking, cycling and transit direction into sequential journey. The planner also features an elevation chart, to accommodate a user’s cycling preferences and carshare locations.

|

A young man got a flat tire while driving at night on a back road. He tried to fix it, but found that the car had no jack. Then he noticed the light of a farmhouse farther up the road. As he walked toward it he thought to himself, Suppose the farmer isn’t home? Suppose he won’t answer the door? Suppose if I ask him for a jack he won’t let me borrow it? Suppose he doesn’t trust me? Why doesn’t he like me? – The more he thought the more upset he got. Finally he reached to the farmhouse door and knocked. When the farmer opened the door, the young man yelled, “O.K. YOU CAN JUST KEEP YOUR OLD JACK!” and stomped away. |

References And Resources For More Information

AIGA (2005), Symbol Signs, American Institute of Graphic Arts (www.aiga.org/content.cfm/symbol-signs). Provides a list of 50 standard symbols for use in buildings, on streets, in transportation terminals, and other locations were people require wayfinding directions.

Troels Andersen, et al. (2012), Collection of Cycle Concepts, Cycling Embassy of Denmark (www.cycling-embassy.dk); at www.cycling-embassy.dk/2013/08/01/cycle-concepts2012.

Louise Baker (2013), A Travel Demand Management Digital Safari, IPENZ Transportation Group Conference, Dunedin, New Zealand; at http://conf.hardingconsultants.co.nz/workspace/uploads/baker-louise-ipenztg2013-a-519196af3bf18.pdf.

Bike Metro (www.metro.net/bikes) identifies recommended bicycle routes from any two addresses in Southern California. It provides specific directions and an elevation profile, based on users’ individual tolerance for hills and traffic. It also calculates the cost of the trip by automobile and the savings cycling, and calories consumed.

Tony Dutzik, Travis Madsen and Phineas Baxandall (2013), A New Way to Go: The Transportation Apps and Vehicle-Sharing Tools that Are Giving More Americans the Freedom to Drive Less, U.S. PIRG Education Fund (www.uspirg.org); at http://uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/A%20New%20Way%20to%20Go%20vUS1_1.pdf.

Dr. Marcus Enoch, Lian Zhang and David Morris (2005), Organisational Structures for Implementing Travel Plans: A Review, Loughborough University, OPTIMUM 2, (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/bitstream/2134/3367/1/enoch%20zhang%20O2%20LPTG%20final%20report.pdf).

Kadley Gosselin (2011), “Study Finds Access to Real-Time Mobile Information Could Raise the Status of Public Transit,” Next American City (www.americancity.org); at (http://nextcity.org/daily/entry/study-finds-access-to-real-time-mobile-information-could-raise-the-status-o).

IOLT (2001), Public Transport Information Websites: How To Get It Right – A Best Practices Guide, Institute of Logistics and Transport (www.iolt.org.uk).

Legible London (www.tfl.gov.uk/microsites/legible-london) is a comprehensive pedestrian wayfinding system that includes integrated signs, maps and websites which all use consistent and easy-to-understand design features.

David Levinger and Maggie McGehee (2008), “Responding to New Trends Through Innovative Design,” Community Transportation, Community Transportation Association (http://web1.ctaa.org).

Chris Lightfoot and Tom Steinberg (2006), Travel-time Maps and their Uses, My Society (www.mysociety.org/2006/travel-time-maps/index.php). This website describes how Travel-time Maps can be used to indicate the time needed to travel from a particular origin to other areas, and compare accessibility by different modes.

John Muhlhausen (2005), Wayfinding Is Not Signage: Signage Plays An Important Part Of Wayfinding – But There's More, (http://myhome.spu.edu/kgz/4209/article1.html).

NextBus (www.nextbus.com) is a private company that uses Global Positioning Systems (GPS) to provide real-time transit vehicle arrival information to passengers and managers in various North American cities.

Project for Public Spaces and Multisystems (1999), The Role of Transit Amenities and Vehicle Characteristics in Building Transit Ridership, Transit Cooperative Research Program Report 46, National Academy Press (www.trb.org).

J. Raine, A. Withill and M. Morecock Eddy (2014), Literature Review Of The Costs And Benefits Of Traveller Information Projects, Research Report 548, NZ Transport Agency (www.nzta.govt.nz); at www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/research/reports/548/docs/548.pdf.

Ridescout App (www.ridescoutapp.com) is

a mobile application that combines all available transportation modes

(carshare, transit, taxi, walking, cycling) into a single interface.

RTA (2002), Producing and Using Transport Access

Guides, produced by the Road and Traffic Authority, New South Wales (www.rta.nsw.gov.au); at www.rta.nsw.gov.au/trafficinformation/downloads/sedatransportaccessguide_dl1.html.

Katherine F. Turnbull and Richard H. Pratt (2003), Transit Information and Promotion: Traveler Response to Transport System Changes, Chapter 11, Transit Cooperative Research Program Report 95; Transportation Research Board (www.trb.org).

RTA (2003), RTA Mobility Management Case Study, Roads and Traffic Authority NSW (www.rta.nsw.gov.au).

Transit App (www.thetransitapp.com) is a mobile

application that provides all nearby transit departures by utilizing GPS and

real time technology.

Transit Website Database (http://its.dot.gov) catalogues transit agencies

that provide information through the Internet.

TTI (1999), A Handbook of Proven Marketing Strategies for Public Transit, Transit Cooperative Research Program Report 50, National Academy Press (www.trb.org).

John Zacharias (2001), “Pedestrian Behavior and Perception in Urban Walking Environments,” Journal of Planning Literature, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 3-18.

This Encyclopedia is produced by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute to help improve understanding of Transportation Demand Management. It is an ongoing project. Please send us your comments and suggestions for improvement.

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

www.vtpi.org info@vtpi.org

1250 Rudlin Street, Victoria, BC, V8V 3R7, CANADA

Phone & Fax 250-360-1560

“Efficiency - Equity - Clarity”

#113